How to Steal an EV (And Why You'll Probably Get Away With It)

How to Steal an EV (And Why You'll Probably Get Away With It)

On February 16, 2026, a 2025 Kia EV6 GT-Line was stolen from Carnex, a dealership in Mississauga. The car was worth $47,000. It had active telematics. It was broadcasting its GPS location to Kia's servers in real-time.

Over the next 48 hours, I would email the President of Hyundai Canada, the CEO of Geotab, a Member of Parliament, and a half-dozen connected vehicle API companies. I'd call the RCMP, the OPP, Peel Regional Police, CBSA, and the national stolen vehicle database.

The car was recovered at a school parking lot. Battery dead. The charger was in the back seat. They were parked next to a 120V outlet.

Stealing an EV in Canada is easy. Not because the technology to stop you doesn't exist. But because nobody can access it.

The Theft

3:11 AM. Family Day weekend. A white BMW M3 with no front plate pulls into the lot. Minutes later, a black Kia EV6 GT-Line drives away. The BMW follows.

The surveillance footage is grainy but clear enough. Two vehicles. Coordinated. Gone before anyone notices.

The EV6 was a recent acquisition — purchased at ADESA Montreal two weeks earlier for $47,200. A Hyundai Capital lease return with 9,644 kilometers on it. Clean Carfax. Quebec plates.

And like every modern connected vehicle, it was equipped with a Telematics Control Unit (TCU) that was actively transmitting GPS coordinates to Kia's backend infrastructure. Every few seconds. Regardless of whether anyone was subscribed to Kia Connect.

The data to locate this car existed from the moment it left the lot.

The Infrastructure That Exists

Your connected car knows exactly where it is. Here's who else has that data:

The OEM (Kia/Hyundai): The vehicle's TCU phones home to Kia's servers continuously. Location, battery state, odometer, diagnostics. This happens whether or not you pay for Kia Connect. The hardware doesn't care about your subscription status.

Telematics Aggregators: Companies like Smartcar and High Mobility have API integrations with major OEMs including Kia. They can pull real-time location data for connected vehicles.

Pleos: Hyundai Motor Group's own connected vehicle platform. They literally have a Vehicle Data API that provides "connected data, including vehicle status information" for Hyundai, Kia, and Genesis vehicles.

Geotab: The Canadian telematics giant powers Kia's commercial fleet platform. They have a partnership with Kia and 42dot for connected vehicle data.

Charging Networks: Electrify Canada, FLO, ChargePoint — every DC fast charge session logs the VIN and location.

ALPR Networks: License plate readers on highways, toll roads, parking lots, and police cruisers across the country.

407 ETR: Ontario's toll highway photographs every vehicle at every on-ramp and off-ramp.

CPIC: The Canadian Police Information Centre — the national database that flags stolen vehicles for every law enforcement agency, border crossing, and port scanner in the country.

The infrastructure to locate a stolen vehicle in real-time already exists. It's been built. It's operational. The data is flowing.

None of it helped.

The Runaround

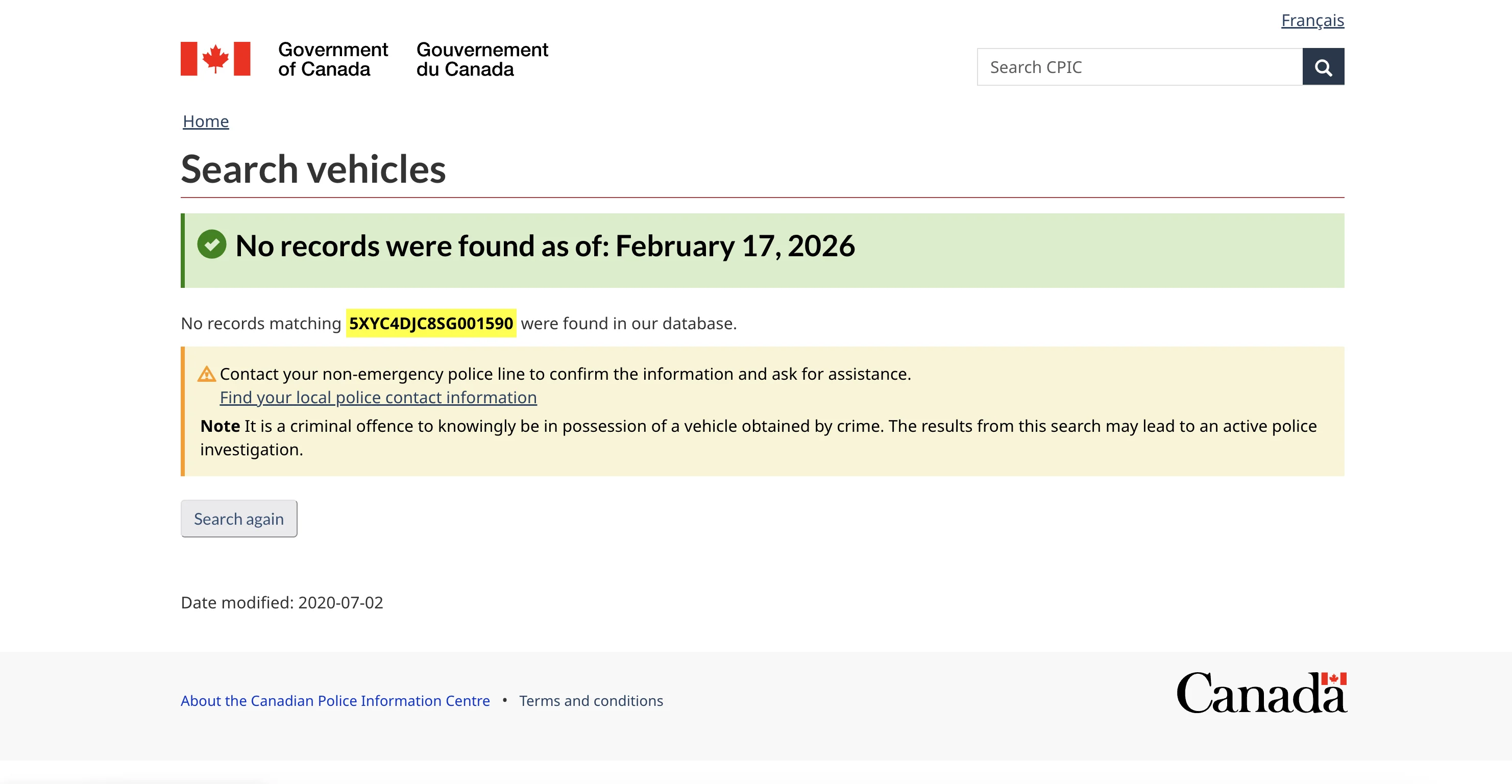

Hour 1-6: Police report filed with Peel Regional. Officer classifies it as a Break & Enter instead of a stolen vehicle. The VIN never enters CPIC.

Hour 6-12: Call Kia Connect's Stolen Vehicle Recovery line. They need account credentials to activate tracking. The account belongs to Hyundai Capital, the previous lessee. The current owner can't access it. Can't activate SVR without completing the OAuth consent flow. Can't complete the OAuth flow without the car.

Hour 12-24: Email Smartcar. They respond quickly — but need the owner to authenticate through Kia Connect. Same problem. Their CEO confirms they don't have data-sharing agreements with Kia Canada anyway.

Hour 24-36: Email the President of Hyundai Canada. Email the CEO of Geotab. Neither can access the data directly. The systems are siloed. The authorization chains are broken.

Hour 36-48: Call CPIC directly. The VIN still isn't in the system. The national stolen vehicle database — the one thing designed to flag this car at every checkpoint from here to Montreal — was never updated.

Why? Because one officer checked the wrong box on a form.

The Phone Tree From Hell

Over 48 hours, the calls went like this:

Peel Regional Police → "Call Project VECTOR" OPP Project VECTOR → "This is Halton's jurisdiction" Halton Police → "This is Peel's jurisdiction" Back to Peel → "The report was filed as B&E, you need to talk to the officer" The Officer → Not available CPIC → "The VIN isn't in our system, contact your local police" Back to Peel → "We'll look into it"

Meanwhile, the car is broadcasting GPS coordinates to servers that nobody will query.

The Recovery

The car was found three days later at a school parking lot. Battery dead.

The charger was in the back seat. They were parked next to a 120V outlet.

The EV6 has a 480-kilometer range. Toronto to Montreal is 540 kilometers. They didn't make it.

Two guys in a modified BMW M3 stole a $47,000 electric vehicle with active GPS telematics, a charger in the trunk, and 480 kilometers of range. They couldn't figure out how to plug it in.

The car was recovered not because any system worked, but because the thieves failed harder than the infrastructure did.

Why This Keeps Happening

Canada has an auto theft crisis. Over 105,000 vehicles were stolen in 2024. The GTA is ground zero. Most stolen vehicles end up in containers at the Port of Montreal within 72 hours, shipped to West Africa and the Middle East.

The technology to stop this exists:

- Real-time GPS from OEM telematics

- API access through connected vehicle platforms

- ALPR networks that can flag plates instantly

- Charging network logs that track EVs by VIN

- 407 ETR cameras that capture every vehicle

But the systems don't talk to each other.

The data is siloed in private companies who won't share it without bureaucratic approval chains that move slower than the thieves. The police can't access telematics without formal requests that take days. CPIC depends on correct report classification by individual officers. The OEMs won't share location data without authorization from accounts that may not even belong to the current owner.

Nobody's job. Everyone's problem.

What Would Actually Work

Automatic CPIC entry. One cop checks the wrong box and a $47,000 car becomes invisible to every border checkpoint in the country. That's insane. Stolen vehicle report filed? VIN hits CPIC. Automatically. No checkbox.

Owner access to their own car's location. I own the car. I have documentation. Give me the GPS coordinates. Not a phone tree. Not a 48-hour runaround. The data exists. Let me have it.

OEM theft recovery that works. Kia has Stolen Vehicle Recovery. It only works if you happen to be the person whose Kia Connect account is attached from three owners ago. That's not a feature. That's a liability shield.

A single theft alert protocol. Charging networks, ALPR, toll roads, OEM telematics — they should all know a VIN is stolen within minutes. Right now they don't talk to each other. At all.

TL;DR

I emailed the President of Hyundai Canada. The CEO of Geotab. A Member of Parliament who chairs the Standing Committee on Public Safety. Called the RCMP, OPP, CPIC, CBSA.

The car was found because the thieves couldn't figure out how to plug it in.

Conclusion

105,000 vehicles stolen last year. $1 billion in losses. A crisis that everyone acknowledges and nobody owns.

Every connected car on the road is broadcasting its location right now. The APIs are live. The networks are operational. The data is there.

And when you call to ask for it, you get a phone tree.

So here's how to steal an EV in Canada: just take it. The odds are in your favor.

Unless you can't figure out the charger.

Have a story about auto theft, connected vehicle data, or the systems that should work but don't? Reach out at hello@cardog.app.