Building a VIN Decoder: A Systems Engineering Deep Dive

Every vehicle sold in North America since 1981 carries a 17-character code that decodes to its complete manufacturing history. This code is queried billions of times annually—by recall systems identifying defective vehicles, insurance companies assessing risk, parts suppliers matching components, and consumers researching purchases.

The system that makes this possible represents 1970s information architecture at its finest: a hierarchical namespace, mathematical error detection, and regulatory coordination across 50+ manufacturers that's maintained backward compatibility for over 40 years.

This is how VIN decoding actually works—and why building an optimal decoder requires understanding regulatory pipelines, global data asymmetries, and mathematical properties most automotive engineers have never considered.

The Check Digit: Mathematical Validation from 1977

Before examining how VIN decoding works, let's start with its most elegant component: position 9, the check digit. This single character validates the entire VIN using weighted modular arithmetic designed when digital communication was unreliable.

The Algorithm

Step 1: Character-to-number translation

VINs use 33 characters (0-9, A-Z excluding I, O, Q to prevent visual confusion). Each maps to a number:

const charValues: Record<string, number> = {

'0': 0, '1': 1, '2': 2, '3': 3, '4': 4, '5': 5, '6': 6, '7': 7, '8': 8, '9': 9,

'A': 1, 'B': 2, 'C': 3, 'D': 4, 'E': 5, 'F': 6, 'G': 7, 'H': 8,

'J': 1, 'K': 2, 'L': 3, 'M': 4, 'N': 5, 'P': 7, 'R': 9,

'S': 2, 'T': 3, 'U': 4, 'V': 5, 'W': 6, 'X': 7, 'Y': 8, 'Z': 9

};Notice the non-sequential mapping: A=1, J=1, P=7, R=9 (skipping Q), then S=2. This isn't alphabetical—it's optimized for error detection. Common transcription errors like B↔8 or S↔5 produce different check digits.

Step 2: Positional weighting

Each position gets a specific weight, with critical positions weighted higher:

const weights = [8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 10, 0, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2];

// pos: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17Why these weights?

- Position 8 gets weight 10 (highest): Last VDS position, most critical for vehicle identification

- Position 9 gets weight 0: This is the check digit being calculated

- Position 10 gets weight 9: Model year is critical

- Descending weights 8→2: Earlier positions (WMI) weighted higher than serial numbers

Step 3: Calculate and validate

function calculateCheckDigit(vin: string): string {

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 17; i++) {

if (i === 8) continue;

sum += charValues[vin[i]] * weights[i];

}

const remainder = sum % 11;

return remainder === 10 ? 'X' : remainder.toString();

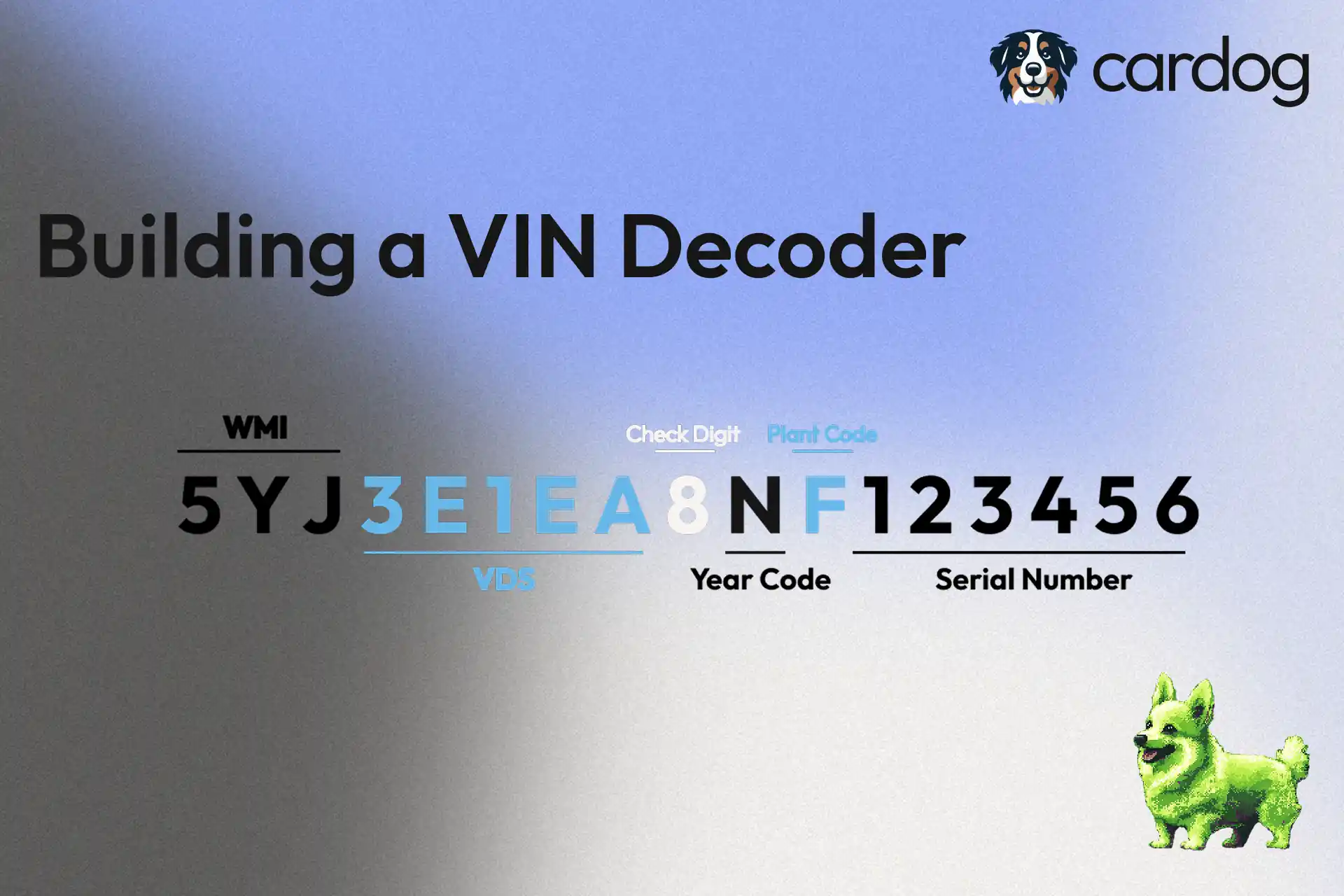

}Example with real Tesla VIN: 5YJ3E1EA9NF123456

Char: 5 Y J 3 E 1 E A 9 N F 1 2 3 4 5 6

Value: 5 8 1 3 5 1 5 1 9 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6

Weight: 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 10 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Product: 40 56 6 15 20 3 10 10 0 45 48 7 12 15 16 15 12

Sum = 310

310 % 11 = 2 (position 9 should be '2' for valid VIN)Why Modulo 11?

NHTSA chose modulo 11 over alternatives for specific reasons:

Modulo 10 (Luhn algorithm, used by credit cards):

- Detects 100% of single-digit errors

- But only ~90% of transpositions

- All results (0-9) are digits—no 'X' needed

Modulo 11 (VIN system):

- Detects ~90.9% of single-digit errors (10 out of 11 substitutions)

- Detects ~98-99% of transpositions (weight differences catch most swaps)

- Result 10 requires 'X', adding slight complexity

- Better overall error detection than modulo 10

Modulo 37 (theoretical maximum):

- Would use all 33 VIN characters + 4 more (including I, O, Q)

- Detects ~97.3% of single-digit errors

- But reintroduces visual ambiguity (I vs 1, O vs 0)

NHTSA chose modulo 11 as the optimal balance between error detection and human readability—accepting that I, O, Q cannot be used to prevent transcription errors from visual confusion.

Why This Matters for Implementation

Every VIN decoder validates the check digit before database lookup:

function decodeVIN(vin: string): VehicleInfo | null {

if (!validateFormat(vin)) return null; // ~100 nanoseconds

if (!validateCheckDigit(vin)) return null; // ~1 microsecond

return lookupDatabase(vin); // ~1-10 milliseconds

}This ordering provides:

- Performance: Reject invalid VINs instantly without expensive database queries

- Load reduction: ~5-10% of queries are transcription errors, caught immediately

- Offline capability: Basic validation without network/database access

The check digit catches approximately 95% of transcription errors before any database operation occurs.

The Foundation: How Vehicles Enter the System

Before understanding decoder implementation, you need to understand how VIN data originates: the 565 submittal process.

What's a 565 Submittal?

Before any vehicle can be legally sold in the United States, its manufacturer must submit Form HS-565 to NHTSA. This comprehensive technical document contains:

- Complete vehicle specifications (dimensions, weights, capacities, performance)

- Safety system documentation (airbags, seat belts, crash ratings, stability control)

- VIN pattern definitions: How each character in positions 4-8 maps to vehicle attributes

- Manufacturing details (assembly plants, production capacity, expected volumes)

Here's Tesla's actual 2025 submittal showing how manufacturers encode their entire product line into VIN patterns.

NHTSA reviews each submittal, assigns VIN patterns, and adds the data to the VPIC (Vehicle Product Information Catalog) database. This creates a prospective data pipeline:

Month 0-3: Manufacturer prepares 565 submittal Month 4-5: NHTSA review and VIN pattern assignment Month 6: Manufacturer updates production tooling Month 7+: Vehicles produced with approved VINs, data already in VPIC

This means VIN decoding data exists before the first vehicle is built. When a new model launches, its VIN patterns are already in NHTSA's database.

The Manufacturer's Encoding Problem

Here's what most engineers don't realize: manufacturers face a combinatorial explosion when designing VIN patterns.

Consider Toyota's 2024 Camry lineup:

- 4 trim levels (LE, SE, XLE, XSE)

- 3 engines (2.5L 4-cyl, 3.5L V6, 2.5L Hybrid)

- 2 drive types (FWD, AWD for some trims)

- 2-3 major option packages per trim

- Multiple manufacturing plants (Kentucky, Canada, Japan)

That's ~80-100 distinct configurations. VDS positions 4-8 provide only 5 characters, each with 33 possible values, for encoding this information: 33^5 = ~39 million combinations.

But manufacturers can't use all combinations—they need patterns that:

- Don't collide with previous model years (carry-over patterns)

- Leave room for mid-year additions (new trims, options)

- Remain logical for service technicians to decode manually

- Align with internal parts/ordering systems

The solution: Hierarchical encoding where each position represents progressively finer specification:

Toyota Camry VIN: 4T1**B11H**XKU******

↑ ↑↑↑↑

Position 4 (B): Body style (sedan, different from Camry wagon)

Position 5 (1): Engine type (2.5L 4-cyl)

Position 6 (1): Specific engine variant/emissions

Position 7 (H): Trim level + restraint systems

Position 8 (X): Transmission + drive typeThis hierarchical approach means partial VIN matching is possible: all 2024 Toyota Camrys with 2.5L engines start with 4T1B1, regardless of trim or options.

Why This Creates Implementation Challenges

The hierarchical encoding means VIN decoding requires:

- Sequential parsing: You must determine position 4 before interpreting position 5

- Context-dependent patterns: The same character means different things for different manufacturers

- Year-range validation: A pattern valid for 2020-2023 might be recycled with different meaning for 2024+

This is why naive pattern matching fails and database-driven decoding is necessary.

The Global Data Asymmetry Nobody Talks About

Here's a fact that shapes the entire VIN decoding industry: The United States is the only major automotive market with comprehensive, free, public vehicle data.

Europe: Comprehensive but Inaccessible

The European Union maintains WVTA (Whole Vehicle Type Approval) data comparable to NHTSA's VPIC. Every vehicle sold in the EU has complete technical documentation... but it's not public.

The restriction isn't GDPR—vehicles contain no personal data. It's bureaucratic inertia. The EU has no mandate for public disclosure, so type approval data remains scattered across:

- National registries (Germany's KBA, UK's DVLA, France's ANTS)

- Manufacturer proprietary systems

- Commercial databases compiled from dealer networks

European VIN decoders exist, but they're patchwork systems with ~90% accuracy versus 99.5%+ for US market vehicles.

Canada: Technically Required, Practically Incomplete

Transport Canada requires CMVSS declarations (equivalent to 565 submittals), but:

- Most data isn't systematically digitized

- No comprehensive public API exists

- Historical data (pre-2010) is largely paper records

- VIN pattern documentation is inconsistent across manufacturers

Canadian VIN decoding works because most vehicles sold in Canada are also sold in the US, so NHTSA's database covers them. Canadian-exclusive models often have incomplete data.

China: Comprehensive and Completely Closed

China's MIIT (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology) maintains detailed vehicle databases, but with zero public access. State-controlled data, different VIN structure (doesn't follow ISO 3779), manufacturer-specific encoding with no standardized decoding.

Export vehicles use ISO-compliant VINs—which manufacturers typically submit to NHTSA anyway for the US market.

The Practical Impact

NHTSA's VPIC database became the de facto global standard for VIN decoding, despite being designed purely for US regulatory compliance. Every commercial VIN decoder—including our Corgi library—primarily relies on NHTSA data.

This creates an interesting market dynamic:

- Decoding US market vehicles: 99.5%+ accuracy, comprehensive data

- Decoding European vehicles: 85-90% accuracy, patchy coverage

- Decoding Asian/other markets: 70-80% accuracy, relies on cross-referencing US exports

If you're building a VIN decoder, you're really building a NHTSA VPIC decoder first, then patching in other data sources as available.

Why This System Saves Lives and Time

The VIN standardization system has quantifiable impact that most engineers don't appreciate.

Surgical Recall Targeting

NHTSA's recall system has issued 70,000+ recalls since 1966, affecting hundreds of millions of vehicles. VIN-based targeting enables surgical precision:

Takata airbag recall (2013-2023):

- 67+ million vehicles recalled

- VIN decoding identified specific production dates with defective inflators

- Instead of recalling "all 2010-2020 Hondas," NHTSA targeted "2015 Honda Accords built at Marysville Plant between production sequence 123456-145678"

- This precision prevented unnecessary repairs on ~40% of vehicles that would have been caught in a broader recall

GM ignition switch recall (2014):

- 30 million vehicles recalled

- VIN position 11 (assembly plant) + positions 12-17 (production sequence) identified specific batches with defective parts from supplier

- Ended a decade-long crisis responsible for 124+ confirmed deaths

The VIN's position 11 (assembly plant) and positions 12-17 (production sequence) enable this surgical targeting. Without VINs, recalls would require either over-inclusive campaigns (wasting billions in unnecessary repairs) or under-inclusive campaigns (missing affected vehicles).

Eliminating Vehicle Ambiguity

The pre-VIN era (before 1981) relied on manufacturer-specific serial numbers with no standardization, body plate data that varied by manufacturer, and vague title descriptions.

Modern VIN system eliminates ambiguity across entire industries:

Insurance underwriting: Automated VIN decode provides instant risk assessment, crash test ratings, theft statistics—replacing manual verification processes that took 15-20 minutes per vehicle.

Parts replacement: VIN lookup ensures correct component specification on first try. Before VINs, mechanics relied on visual inspection and paper catalogs, resulting in frequent wrong-part orders and returns.

Fleet management: VIN-based automated systems replace manual spreadsheet tracking, enabling real-time maintenance scheduling and compliance monitoring.

Used vehicle transactions: VIN verification ensures listing accuracy, dramatically reducing post-purchase disputes over specifications.

While exact quantification is difficult (the pre-VIN baseline no longer exists), industry estimates suggest the system has saved hundreds of millions of person-hours across these sectors over 40+ years.

Implementation Approaches: The Trade-offs

Now that we understand the regulatory foundation and why VIN decoding matters, let's examine how to actually build a decoder.

Approach 1: The NHTSA VPIC Database

NHTSA publishes the complete VPIC database (~1.5GB) for download. The schema is a normalized relational design:

-- Core tables (simplified)

Wmi (Id, Wmi, ManufacturerName, VehicleType, Country)

VinSchema (Id, Name, SchemaType)

Wmi_VinSchema (WmiId, VinSchemaId, YearFrom, YearTo)

Pattern (Id, VinSchemaId, ElementId, Position, Keys, ElementValue)

Element (Id, Name, Description)Decoding algorithm:

- Extract WMI (positions 1-3) and year (position 10)

- Query

Wmi→Wmi_VinSchema→VinSchemawith year validation - For each VIN position, query

Patterntable for matching character - Join results to get complete vehicle specification

Performance characteristics:

- NHTSA VPIC API: ~3,000ms per decode (over network, includes latency)

- Local VPIC database: ~150-300ms per decode

- With optimized indexes: ~50-100ms per decode

Pros:

- Complete coverage, official data

- Handles all edge cases

- Includes comprehensive historical data

Cons:

- 1.5GB size impractical for browsers/mobile

- Slow queries (minimum 4-5 table joins)

- Contains data most applications don't need

This is the reference implementation but not optimal for production.

Approach 2: Optimized SQLite (Corgi)

Corgi's approach aggressively optimizes the VPIC database:

- Remove unnecessary tables: Drop 847MB

WMIYearValidChars(redundant), specialty vehicle tables (buses, motorcycles), safety feature tables - Prune patterns: Keep only essential elements (make, model, trim, engine, body style)

- Optimize indexes: Read-optimized composite indexes for common query patterns

- Aggressive VACUUM: Rebuild database from scratch to eliminate fragmentation

Results:

- 1.5GB → 64MB uncompressed → 21MB compressed (97.9% reduction)

- Query time: 150ms → 12ms average (12x faster)

- Works in browsers, Node.js, edge workers

This is the current production standard for most applications.

Approach 3: Theoretical Optimum—Pre-Computed Binary Lookup

What if we pre-computed every valid VIN and stored results in a binary format optimized for O(1) lookups?

The key insight: VINs have a bounded search space that's smaller than it appears.

- Position 1-3 (WMI): ~36,000 assigned codes

- Position 4-8 (VDS): Manufacturer-specific, sparse patterns (~100-500 per manufacturer)

- Position 9: Check digit (calculated, reduces space by 11x)

- Position 10: Year (30 valid codes)

- Position 11: Plant (10-50 per manufacturer)

- Position 12-17: Serial number (doesn't affect specifications)

Actual search space: Only ~500M-1B unique combinations of positions 1-11 that map to distinct vehicle specifications. Serial numbers (positions 12-17) don't affect decoded data—a Tesla Model 3 serial 000001 has identical specs to serial 999999.

Architecture:

- Pre-compute all valid 11-character prefixes (positions 1-8, 10-11, excluding check digit)

- Build perfect hash table (bijective mapping, no collisions)

- Store results in packed binary format (64 bytes per record)

- Use memory-mapped I/O for zero-copy reads

Performance:

- Lookup time: ~1-2 microseconds (hash + memory read + string table lookup)

- Storage: ~500M records × 64 bytes = 32 GB uncompressed → ~2-4 GB compressed

Trade-off: This trades massive storage (100x larger than Corgi) for extreme performance (10,000x faster). Makes sense for:

- High-throughput systems (decode millions of VINs/day)

- Edge computing (sub-millisecond latency requirements)

- Real-time telemetry (autonomous vehicles, fleet tracking)

But not for browsers, mobile apps, or most server applications where Corgi's 12ms latency is perfectly acceptable.

Comparison Summary

| Implementation | Size | Query Time | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHTSA VPIC | 1.5 GB | 150-300ms | Reference only |

| Corgi (SQLite) | 21 MB | 8-15ms | Production standard |

| Binary lookup | 2-4 GB | 1-2 µs | High-throughput systems |

| NHTSA API | 0 MB | 3,000ms | No local storage |

For most applications, Corgi represents the optimal balance. The binary approach is fascinating but overkill unless you're processing millions of VINs daily.

What You Don't Learn from Textbooks

How VINs Are Generated on Production Lines

Automotive assembly lines produce one vehicle every 45-90 seconds. VIN assignment happens at a specific control point—usually after the body shell is welded but before painting.

The system:

- Central VIN server at each plant maintains the production sequence counter

- Assembly line controller requests next VIN for the vehicle configuration about to be built

- Server generates VIN: WMI (fixed) + VDS (from build spec) + check digit (calculated) + year + plant code + sequential number (incremented)

- Physical stamping: VIN plate attached to dashboard, stamped into frame rail

- Digital tracking: VIN linked to build sheet, quality checkpoints, shipment tracking

The critical detail: The sequence counter (positions 12-17) resets to 000001 at the start of each model year, not calendar year. A plant might produce 2024 and 2025 model year vehicles simultaneously, using separate sequence counters.

This is why VIN lookups require knowing the model year—the same sequence number appears in multiple years.

What Happens When VIN Patterns Collide

Occasionally, manufacturers submit 565 patterns that collide with existing assignments. NHTSA's system catches most collisions automatically, but edge cases occur:

Scenario: Manufacturer used pattern "XYZ" for 2018-2020. They want to reuse "XYZ" for 2024 with different meaning.

NHTSA's approach:

- Verify no active recalls on old pattern (collision would confuse recall targeting)

- Check 3+ year gap between uses (prevents confusion in used vehicle market)

- Require manufacturer documentation of the pattern reuse

- Add temporal validation to VPIC database (

YearFrom,YearTocolumns)

VIN decoders must handle this by always validating year ranges—the same VIN prefix can mean different vehicles depending on model year.

The Economics Nobody Discusses

NHTSA charges $0 for 565 submittals. Zero. The entire regulatory system is funded by taxpayers.

This creates interesting market dynamics:

- Manufacturers: Submit hundreds of pattern variations (costs them nothing)

- NHTSA: Limited resources for reviewing ~2,000+ annual submittals

- Decoder implementers: Must handle manufacturers who submit overlapping or redundant patterns

Compare this to European WVTA fees (€20,000-€50,000 per vehicle type), which incentivizes manufacturers to minimize pattern variations. This partially explains why European VIN data is more sparse—manufacturers pay to submit data, so they submit less.

The US system's zero cost created the most comprehensive vehicle database in the world, at the cost of occasional pattern redundancy and complexity for decoder implementations.

Building Your Own: Practical Recommendations

For learning / small projects: Use NHTSA's API directly or deploy Corgi:

npm install @cardog/corgiFor production applications (< 10K decodes/day): Corgi's 21MB database and 12ms latency are more than sufficient.

For high-throughput systems (> 1M decodes/day): Consider building specialized infrastructure:

- Cache most-common VIN prefixes in memory (95% hit rate with ~100MB cache)

- Use Corgi as fallback for rare vehicles

- Deploy to edge workers (Cloudflare Workers + D1) for geographic distribution

For ultra-low-latency requirements (< 1ms): The binary lookup approach becomes viable. But this requires:

- Infrastructure for 2-4 GB database distribution

- Monthly rebuild pipeline for NHTSA updates

- Custom perfect hash implementation

For 99% of applications, Corgi represents the optimal trade-off between performance, size, and maintainability.

The Engineering Legacy

The VIN system represents 1970s systems engineering excellence. Faced with the impossible task of creating a universal vehicle identifier that would work across manufacturers, countries, and decades with no pre-existing digital infrastructure, NHTSA's engineers created something remarkable:

Design constraints that became strengths:

17-character fixed length enables physical stamping and creates predictable data structures

Hierarchical namespace (WMI → VDS → VIS) allows delegation while maintaining global uniqueness

Mathematical validation (check digit) enables offline verification without database access

Manufacturer flexibility within standardization balances regulatory oversight with practical encoding needs

30-year model year cycle handles foreseeable future while maintaining single-character encoding

These constraints created a system that scales from metal stamping to 5G telemetry—designed before the internet existed, yet perfectly adapted to modern computing.

The elegance lies not in algorithmic complexity but in how much information can be encoded, validated, and decoded using simple mathematical operations and hierarchical lookup tables.

What Comes Next

Modern automotive systems—connected car telemetry, autonomous vehicle networks, digital vehicle passports—still depend on this 17-character foundation designed when automotive computers were exotic accessories.

The VIN will evolve from a static identifier to a live API endpoint. Tesla already demonstrates this: their VIN links directly to over-the-air update history and diagnostic data. Expect:

- VIN-based vehicle telemetry APIs becoming standard across manufacturers

- Real-time recall notifications pushed to vehicle computers via VIN lookup

- Blockchain-based title transfer using VIN as primary key

- EU's proposed digital vehicle passport creating complete lifecycle tracking by VIN

But the underlying 17-character structure will remain. Changing it would break 40+ years of infrastructure that's embedded in everything from insurance systems to recall databases to parts ordering systems worldwide.

Every time you decode a VIN, you're querying a system that took decades to standardize globally, enables surgical recall targeting that saves lives, and eliminates incalculable person-hours of manual vehicle identification labor.

At Cardog, we built Corgi because this remarkable system deserves tools that match its elegance—fast, accurate, accessible to anyone building automotive applications.

If you're building something that needs VIN decoding: npm install @cardog/corgi

The code is open source. Because the best engineering infrastructure should be available to everyone.